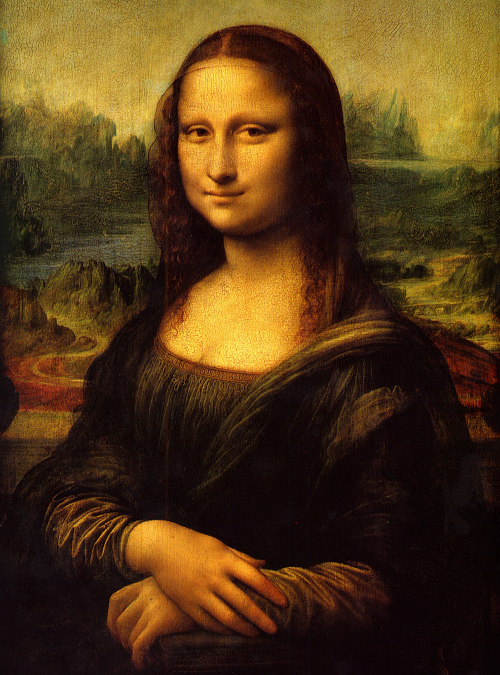

A lot of attention in the recent UK budget has been focussed on the launch of “lifetime ISAs” (or “LISAs” – yes, that’s the reason for the picture…). On the face of it, these seem very tax-efficient. For every £4,000 invested, the Government adds another £1,000. Given that the basic rate of tax is 20%, this looks like you’re getting your basic rate tax back. And then there’s no more tax to pay, on accumulation or on withdrawal – provided no withdrawals are made before age 60. But how does the LISA actually compare with pensions?

For a basic rate taxpayer, an auto-enrolled pension is still better than a LISA, thanks to employer contributions. But ignoring the contributory aspect, the impact of tax on a LISA and a pension is remarkably similar. The best way to look at this is to ignore any investment returns and compare what goes in with what comes out.

A basic rate taxpayer earning £100 will have £20 taken off for tax, and another £12 taken off for National Insurance. This will leave them with £67 net. For a LISA, the Government would increase this by 25%, which is an additional £17. This mean getting £85 out of a lifetime ISA for every £100 gross. For a pension, for every £100 gross put in – which gets relief from both income tax and national insurance – 25% of this is taken tax free at retirement and the remained is taxed at the employee’s marginal rate. For a basic rate taxpayer with a 20% marginal rate, this is equivalent to an effective tax rate of 15%. So again, £100 gross earned gives £85 net.

However, under auto-enrolment, the employer puts in another £100 for every £100 gross contributed. This would mean an individual would be taking out £170 rather than £85. Even when auto-enrolment contribution rates rise, and the employer’s proportion of the total contribution falls, an individual would end up with £136 at the end.

For a higher rate taxpayer who expects to be a basic rate taxpayer in retirement, the pension wins even ignoring any employer contribution. The combined impact of tax and National Insurance for a higher rate taxpayer mean that an individual would get only £72.50 out of a LISA for every £100 gross, whilst the basic rate tax in retirement would still mean £85 being earned in the pension. For higher rate taxpayers expecting to remain so in retirement, the pension outcome falls to £70, so the decision is more finely balanced – again, if employer contributions are ignored.

Of course, there is a chance that LISAs are brought within the remit of auto-enrolment, in which case the advantage of pensions evaporates. However, the issue of employer National Insurance contributions then becomes relevant. This would need to be taken into account either by exempting employer AE-LISA contributions from National Insurance, or by setting them at a level that would make the post-National Insurance cost to the employer similar for pensions and LISA.

In the end, value for money is unlikely to be what drives the success – or failure – of the LISA. The relative attractiveness of LISAs and pensions is more likely to be driven by access rather than value. But it is important to understand where the best results lie, not least so savers know how to make the most of their savings.

![]()