This week I published a paper looking at the history – and future – of the UK State Pension. I came to the conclusion that to keep this benefit affordable, some means testing would ultimately be necessary. This conclusion was controversial, but I still believe it to be correct; I explain why below.

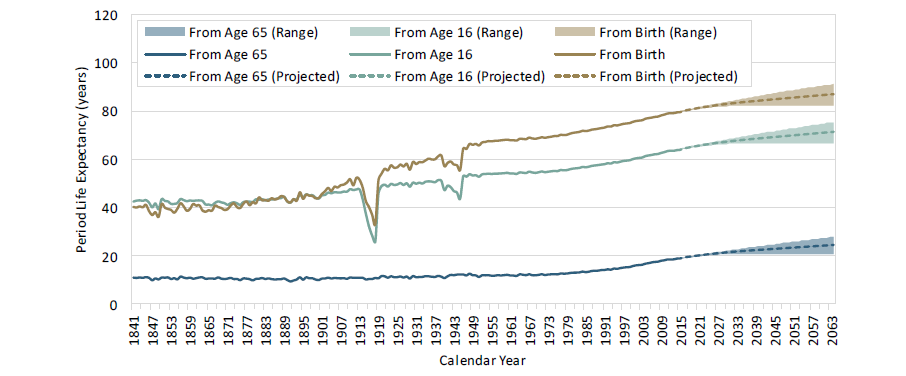

1. People are living longer…

This is not news, but it is obviously important. Longevity has been increasing for more than a century. But the pattern of increases is worth noting. Much of the increase in the early 20th century came from reductions in child mortality; increases in longevity for older women only really started to happen in the 1940s, and for older men in the 1980s.

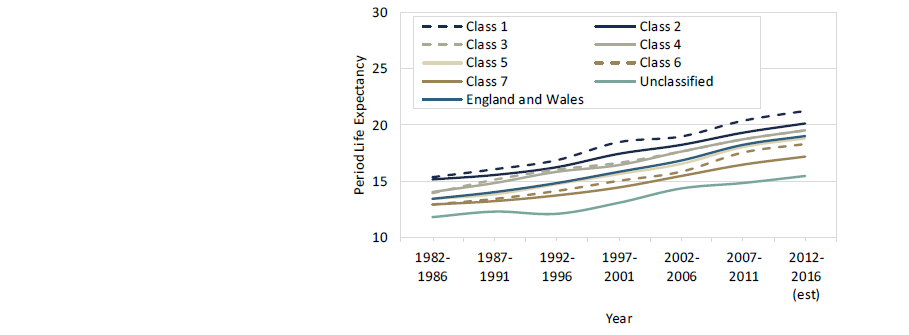

Period Life Expectancy, England & Wales – Males

Source: Human Mortality Database, Office for National Statistics; author’s calculations

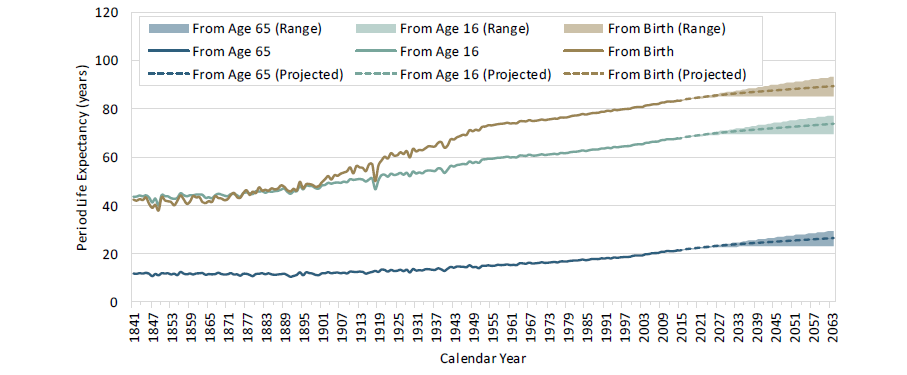

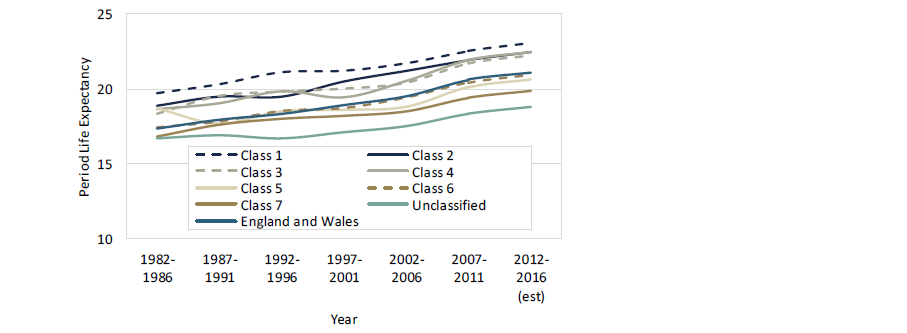

Period Life Expectancy, England & Wales – Females

Source: Human Mortality Database, Office for National Statistics; author’s calculations

This has meant that the phenomenon of the ageing population is actually only a few decades old, and it has two effects. The first is that it means people are likely to spend longer in retirement; the second is that the retired population is likely to grow.

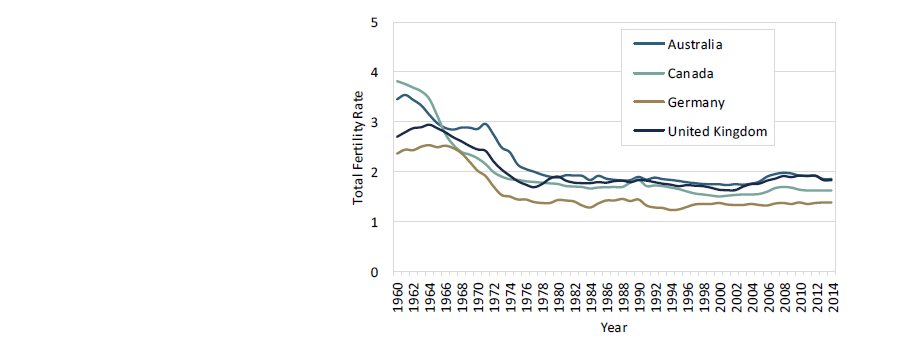

2. …fewer children are being born…

It’s also worth noting that the retired population is growing as a proportion of the total population. This is not just because people are living longer, but also because fewer children are being born. This has been the case for some time, but it does mean that the working population will not be growing at anything like the rate needed to support the current level of pension benefits.

UK Total Fertility Rate

Source: Office for National Statistics; author’s calculations

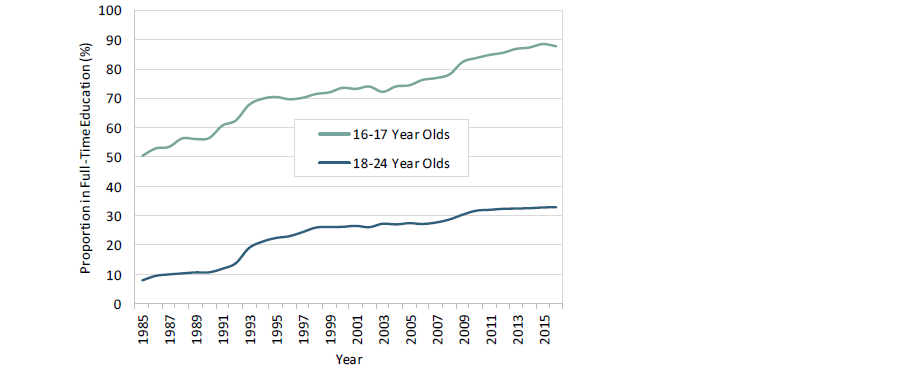

3. …and they are spending longer in full-time education

It is a good thing that levels of education are rising – and they have risen significantly. For example,only half of all 16-17 year-olds were in full-time education in 1985; now, the proportion is almost 90%. And for 18-24 year-olds, the proportion has risen from less than 10% to more than 30% over the same period. But for the period that they are studying, they will not be paying taxes and supporting the pension system.

Proportion of Children and Young Adults in Full-time Education

Source: Office for National Statistics; author’s calculations

So all of this means we should raise the State Pension Age, right?

4. …but the better off are living longest

Well, maybe not. The life expectancy of the wealthiest is significantly higher than that of the poorest. And if the State Pension Age is increased too quickly, the main effect will be to ensure that a higher proportion of the benefits will go to the wealthiest – and that an increasing proportion of the poorest will not even reach state pension age

Male Period Life Expectancy from 65 by Socioeconomic Group

Source: Office for National Statistics; author’s calculations

Female Period Life Expectancy from 65 by Socioeconomic Group

Source: Office for National Statistics; author’s calculations

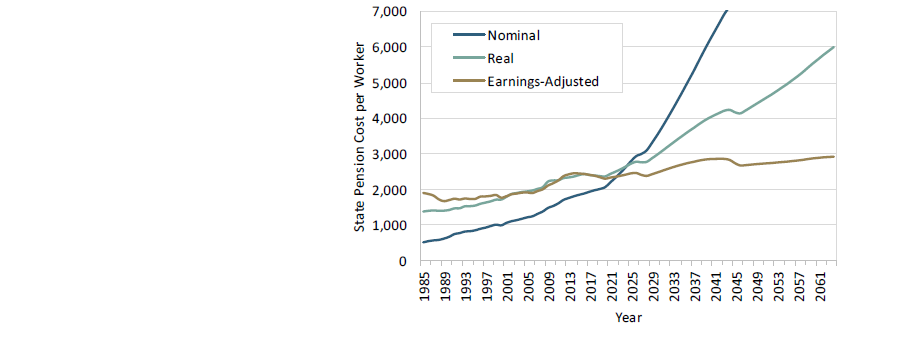

5. Even with planned increases to the State Pension Age, the cost of the State Pension is increasing – and will continue to increase

Even if this argument doesn’t convince you, another might – that the proposed increases to the State Pension Age will not be enough to control costs. The UK State Pension system follows a pay-as-you-go (PAYG) approach. This means that the working population effectively funds the pensions paid to the retired population. As such, considering the cost per worker of the State Pension – in constant earnings terms – seems like an appropriate metric. Under this measure, the cost can be seen to have risen from under £2,000 per person in the mid-2000’s to £2,500 today – and it is projected to rise to nearly £3,000 per person by 2040, even with the proposed increases in the State Pension Age.

Cost per Worker of the UK State Pension

Source: Office for National Statistics; author’s calculations

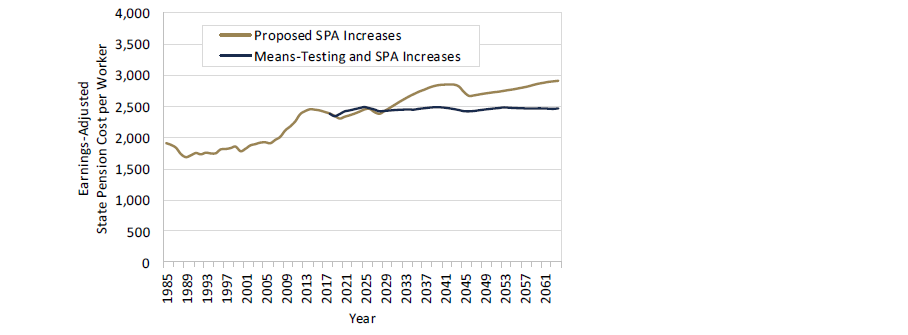

6. So the only solutions are faster increases to the State Pension Age, or means testing

Strictly speaking, these aren’t the only solutions – just the most palatable. It would also be possible to cut the Basic State Pension and New State Pension, or to cap increases, but such moves would be perverse. Or we could accept that these benefits will just get more expensive, and the working population should just pay up. But members of the younger generation are already financially stretched, being less likely to own their own home or to benefit from a final salary pension system, so this too would seem perverse.

The increases in the State Pension Age required to keep the cost per worker at £2,500 would be brutal – a State Pension Age of 69 by 2040, and of 70 (and still increasing) by 2055. As explained above, this would hit the poorest workers hardest.

An alternative is means testing. In fact, if pensions paying higher-rate tax gradually lost their entitlement to the Basic State Pension or the New State Pension – but still retaining their rights to accrued Additional State Pension – then the State Pension Age could rise even more slowly than is currently proposed, reaching 67 in 2035, 68 in 2045 and 69 in 2063.

Cost per Worker of the State Pension after Means Testing

Source: Office for National Statistics; author’s calculations

Conclusion

So, whilst increases to the State Pension Age might be inevitable, they should be treated with caution. And it should be noted that they will not, on their own, enough to control the cost of State Pension provision. For this, means testing may be the most palatable of the options available.

The paper “Surfing the Tsunami: A Plan for State Pension Reform” can be downloaded here; hard copies are also available here.

![]()